I have a few starting points for my genealogy. This isn’t actually the first starting point, but it’s the first I’m going to write about.

Last year, Gram and Gramps handed a package of papers to me. They wanted to make copies or scan them into the computer. It was a bunch of stuff related to Gram’s family in Sweden. It’s really a mixed bag. Some of it was Gram’s own notes. Some of it was some pedigree trees and family group sheets for the Nordvalls (her mother’s side of the family). One was a poster sized pedigree tree for the Omans (both her mother and father’s side of the family). They gave me some other stuff later on, but that was the start.

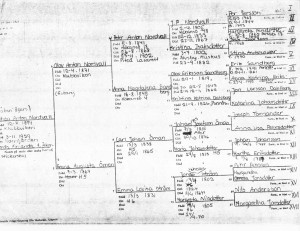

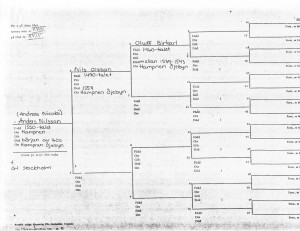

This is one of the Nordvall pedigree trees. The other trees continue people from the top of this one. It’s for Johan Anton Nordvall, who was Gram’s uncle. I assume this was prepared for one of his kids or grandkids. These sheets are 1960s or 1970s era photocopies. The paper clip holding them was rusted even. The form is in Swedish, which is not surprising. Gram’s family is from Piteå, in northern Sweden.

The earliest in time these sheets go is around 1460, with Oluff Birkarl. That actually predates the history I have on the Hathaway side of my family, which I already knew about and which goes back to the late 1500s.

But here’s the rub, it may not be correct. How many people claim to be part Indian these days? Many of them aren’t making it up, even if it’s not true. It’s what their parents told them and their grandparents told their parents. Oral history has a way of getting munged. The same could easily be true for all this information, despite the precision of the dates.

In fact, one of these sheets has information I know is incorrect.

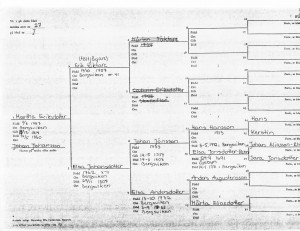

This portion of the tree, 10 generations back from me, has Elsa Jonsdotter-Rehn married to Hans Hansson and having a child named Johan Jönsson.

A quick history of Swedish names. Until the 1800s, most Swedes did not have a family surname. A surname in Sweden was a version of your father’s name. If you were the son of Erik, your last name was Eriksson. If you were the daughter of Lars, your last name was Larsdotter. Surnames did not pass multiple generations.

Like English, old Swedish spellings were flexible. I’ve seen Olof spelled multiple different ways. But while spellings were flexible, Johan Jönsson is probably not likely the son of Hans Hansson. Later sources I’ve found indicate that Johan Jönsson was the son of Elsa Jonsdotter Rehn and Jöns Tomasson. The rest of the tree could have similar errors.

In this case, I’m pretty sure this isn’t a case of family legend passed down badly. Rather, it’s probably a problem with someone trying to match children with parents in the records. With the Swedish naming system, there could be a lot of people with the same name, and Hans looked close enough. Or it was a transcription error. When genealogy is done by hand, it can run into many problems similar to family stories getting changed as they pass down.

But I didn’t know all this at the time. Nevertheless, it was a good starting point for what I was doing.